Effective Orthotic Therapy for Painful Cavus Foot

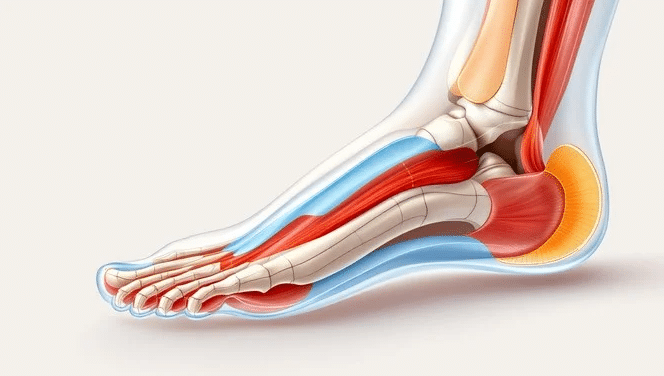

A Randomized Controlled Trial Patients with a cavus or high-arched

Looking through a connective-tissue lens

Steven Gillingham, BSc MSc DPM — The Footnote / Southwest Foot & Ankle Centre (WA, Australia)

Article sourced from The Footnote

If you treat feet long enough, you meet the patient who makes textbook categories feel flimsy: beautiful arches that collapse after lunch, tendons that protest every training block, ankles that sprain when the breeze changes direction, and “flat feet” that are somehow strong in the gym yet unreliable on the stairs. That paradox lives at the intersection of connective tissue biology and load management, the hypermobility lens and it’s where progressive collapsing foot deformity (PCFD) stops being a vague bucket and becomes a set of solvable problems.

This article expands my recent symposium talk into a practical read for clinicians who already speak “hypermobile” and want sharper, clinic-ready moves. I’ll follow the scaffolding from the talk and why it matters, a pragmatic definition of hypermobility, a unifying pathomechanics story of PCFD, age-and-stage nuances in kids, red flags, the handful of tests that actually change decisions, and the treatment triad I come back to every day: align, protect, load.

Because the words we reach for shape the care we deliver. “Flatfoot,” “pronation,” and “instability” are useful descriptors; they’re not mechanisms. Patients who sit somewhere on a hypermobility spectrum from “functionally bendy” through generalised joint hypermobility (GJH) to heritable disorders like hEDS/HSD, often get advice that’s either too fatalistic (“you’re just hypermobile”) or too local (“you need arch support”). In reality, most presentations make sense if you zoom out to connective tissue quality, motor control strategies, and load history over time. That lens gives you reasons, not just labels.

Clinically, I define hypermobility as excessive passive range for age/sex/ancestry in one or more joints plus atypical tissue behaviour under load which includes “giving way,” rapid end-range drift, or delayed force transfer that the patient experiences as fatigue, ache, or “floppy weakness.” We then ask: Is it local or generalised? Lifelong or acquired? Benign or part of a syndrome? That short flowchart prevents the two common misses:

PCFD is not just “arches falling down.” It’s a systems problem that shows up locally. A hypermobility lens adds three recurring ingredients:

Once you see this triad, “flatfoot” stops being a shape and becomes a recoverable dynamic for many patients.

When your mechanism sense says “connective tissue,” your differential should stay wide enough to catch the important stuff:

Keeping these buckets visible makes your plan safer and your patient education more honest.

Most paediatric “flatfoot” is developmentally appropriate, especially in the under-eight crowd. Add hypermobility, and you’ll see wider bases, faster end-range drift, and fatigue with long days. The questions that separate reassurance from deeper work-up:

In kids, the goals are energy efficiency, confidence, and skilled play — not “fixing” an arch. Devices are tools for learning, not prostheses for life.

These are not “don’t treat” flags, they’re “don’t treat alone.”

You don’t need an hour, but you do need signal:

I use this order deliberately. Alignment is not orthotics-worship; it’s giving levers a chance. Protection is time-bound, not learned helplessness. Loading is graded skill + strength, not vibe-based exercise.

1) Align (make force transfer possible)

2) Protect (buy tissue quiet and motor clarity)

3) Load (own alignment through strength & skill)

1) The runner who “can’t feel push-off.”

30-something with GJH, two prior “tib post” flares. In clinic, prolonged late-stance pronation and toe gripping; calf raise weak and painful. With manual midfoot squeeze and heel neutral, calf raise becomes strong and quiet. We commit to firm counter footwear + medial posting shell (for 12 weeks), protect with run-walk swaps and step-count caps, and load with heavy-slow calf + tib post bias + short-ground-contact hops. Four weeks: pain calm, cadence up; 12 weeks: shells become race-day only.

2) The postpartum teacher with end-of-day collapse.

Device window and shoe change reduce “end-range living.” We change the day (sit-to-stand task breaks, staff-room calf raises, pram-walk hills out, flats in) while we teach a tripod that survives fatigue. Language matters: “You’re not broken. Your tissues are permissive right now; we’ll teach your system to share the load again.”

3) The 10-year-old “slow runner.”

Benign mechanics + hypermobility + fatigue. Orthoses for a season to create stability at school, then turn them into a game: hop courses, skipping tricks, single-leg balance challenges. Parents track “keeps up at recess” and stumble counts. The arch will do what arches do; function is the goal.

Patients arrive with foot shapes; they leave with movement stories. If we help them write better ones — with clear mechanisms, time-bound supports, and skills that stick — the arch tends to behave, the tendon tends to forgive, and the person tends to get their life back. That’s the work. That’s the gift.

This article follows the structure of my Hypermobility & Flatfoot symposium presentation and extends it for clinic use.

A Randomized Controlled Trial Patients with a cavus or high-arched

Patient: Female, 14 years, 105 lbs Complaints Redness, pain and

We normally post articles about specific pathologies or cases of

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |